I often marvel at how, despite the comforting lies we tell ourselves, there’s nothing new under the sun. As an example, take The Duckbill Group’s business of optimizing cloud bills. Our spiritual predecessors are about as old as I am. In 1984, when AT&T (“Ma Bell”) was broken up into the baby bells, complexity rapidly spiraled, and in 1985, a company called Telenalysis started auditing corporate long distance bills. There was huge money there—just ask someone about long distance calling hours back then to get a taste of the complexity. We stand on the shoulders of giants, etc.

This of course leads me to GenAI.

GenAI Economics: History Repeats

In today’s GenAI landscape, a whole bunch of the not-quite-leading models are advertised under the aegis of being economically advantaged. “Sure, it’s no Claude Sonnet, but Amazon Nova is quite competent,” says AWS, subtextually. They’re right! Nova is a fine model! But Claude is better, so I’ve never used Nova for anything beyond a couple of tests.

Biasing for frontier models isn’t simply “Corey being weird,” it’s a broad trend. Contrary to what we hear from most companies in 2025, GenAI is still in a place of “will this add value to my workloads?” There aren’t (yet) many scaled-out, steady-state workloads that can be viewed through a lens of long-term planning. Folks are still seeing how and if this emerging technology fits, and approximately none of them is far enough along in that innovation exercise to begin earnestly focusing on improving their cloud economics. The exceptions are few and far between, because “does it work at all?” is where folks are investing their energies, rather than “how do we save money on this thing?”

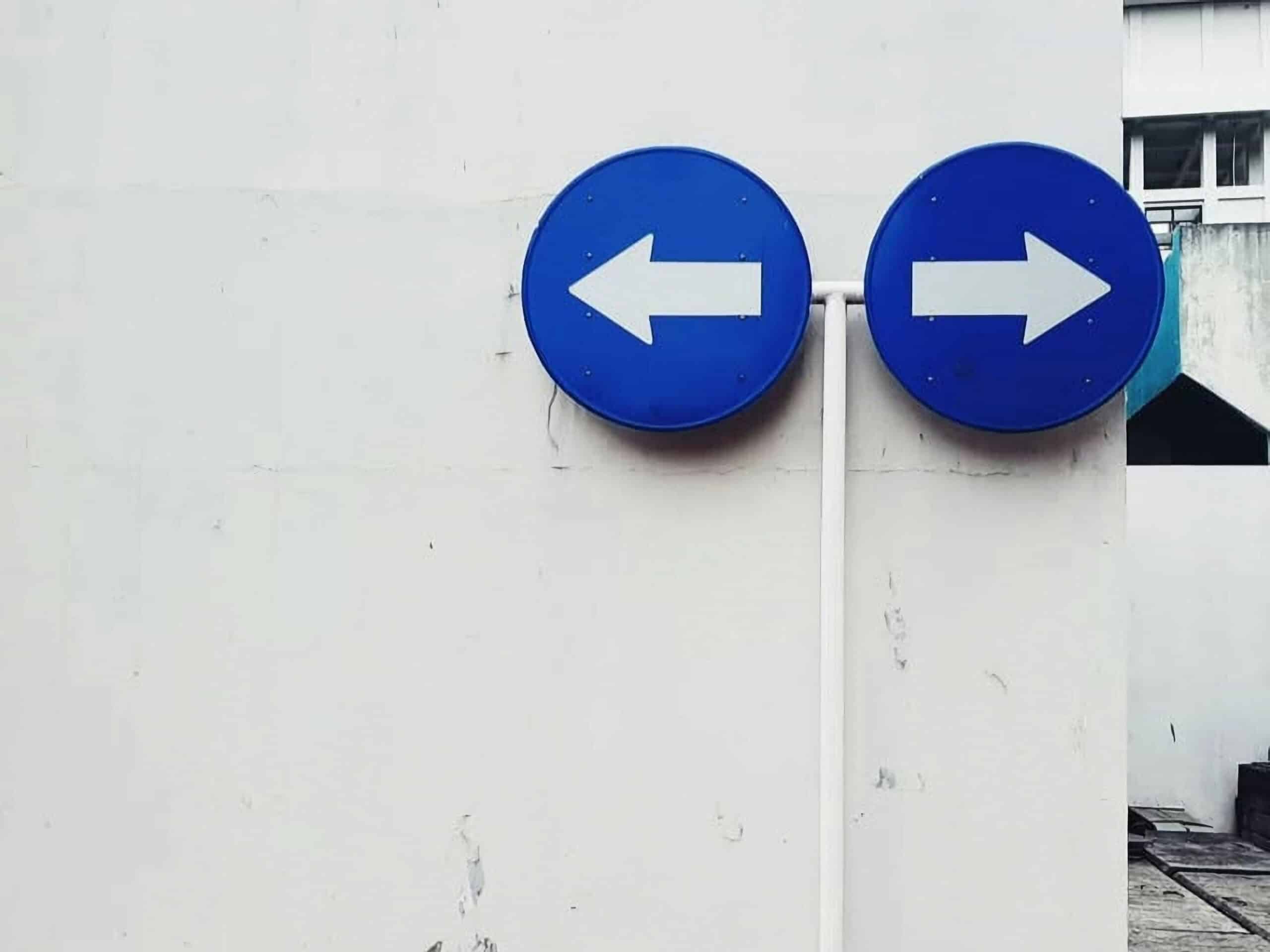

There’s a Continuum

Here’s something we’ve seen play out with remarkable consistency the entire time we’ve been in business. There’s a continuum, with “Innovation” on one end and “Efficiency” on the other, and any given company, project, initiative, or team gets to figure out where on that continuum they want to fall. It isn’t a one-way door; where someone lands on the continuum can be remarkably fluid. But at its heart, these two attitudes are fundamentally opposed.

There is a time and a place for both attitudes here.

Companies fall all over themselves to self-describe as “innovative,” but innovation for its own sake isn’t some kind of moral imperative. I’m writing this post inside of Google Docs, and keep getting interrupted by AI enhancements. I don’t want this brand of innovation; I want what the product was when it was at its best a few years back. Look at the modern iterations of Slack and Dropbox as two more examples; can anyone seriously claim those products are better at serving the customer needs today than they were in the past?

At the same time, I’ve yet to see companies find success using the mindset of “I must build this new thing for the absolute least amount of money possible.” Look at SpaceX; I’ve lost track of how many boosters they’ve smashed into the ocean, the landing pads, and the droneships. Each one of those things costs millions upon millions of dollars. They’d not be where they are now if they hadn’t made that innovation investment.

Even so, any engineering manager can attest that extreme innovation in the form of “letting engineers create” tends towards “fearsomely expensive.” Optimization is important, and I don’t really need to explain to you why “setting all the money on fire without regard to how you’ll afford to run the company tomorrow” is a bad thing.

Finding Your Balance

The pattern I like, and recommend to clients, is having periodic optimization passes through their environments. “Yes, you can go ahead and take chances; get messy; make mistakes!” And then it’s time to periodically clean up after yourself. Otherwise, you find yourself in untenable circumstances of “we have no idea what that cluster is doing, or has been doing since 2012, but it’s huge and we’re scared to touch it.” Maybe it’s a dev environment from someone who’s long since left the company—but maybe it’s your transactions database that somehow never got documented. Spend a few minutes tidying your house every day and you won’t have to spend all weekend cleaning up a disaster area.

The innovation-efficiency continuum isn’t about choosing one extreme or the other permanently. It’s about understanding where your organization needs to be at any given moment. For newer projects or emerging technologies like GenAI, leaning toward innovation makes sense: explore, experiment, and accept that efficiency won’t be your primary concern—for now. For mature workloads or during economic tightening, shift toward efficiency without completely abandoning the ability to evolve.

I’ve consistently observed that the most successful organizations don’t treat this as an either/or proposition but rather as a cyclical process. They innovate, then optimize, then innovate again. They recognize when it’s time to clean up technical debt and when it’s time to make a mess in the pursuit of something better.

It’s important to remember that both innovation and optimization have their place. The trick isn’t choosing one and sticking to it—it’s knowing when to apply each approach, and having the organizational maturity to shift between them as circumstances demand.

Innovation is expensive, but choosing efficiency too early is even more expensive.